The Value of Linguistic Analysis in Philosophy

What role does language play in the analysis and discussion of Philosophy?

Philosophy, a field of emerging thoughts, must solidify its abstract concepts into language, generating dictionaries of new terms to establish their innovative ideas or redefine past ones. The abstract, a free-fall in a landscape of intangible thought, is therefore strung to the “real world” by the thin string of language, connecting the figurative to the verbal-physical and explaining the indemonstrable. Hate and love ebb and flow with the emergence of new vocabulary, as do understanding and confusion; yet many question whether the syntactic fabric of new reasoning – its language – can be completely trusted, or if reliance between word and thought can mean that abstract philosophical principles only hold truth within their own words.

This is an especially relevant discussion topic for philosophy surrounding what can only be explained, as of today, through linguistic communication – most notably many existentialist and theological arguments – which with the invalidation of their mode of explanation would arguably stand no ground. Additionally, self-referential statements, or statements that are only true due to their own definitions, like if this statement is true, then 2+2=5, are especially dangerous if their syntax is disregarded. The value of the medium through which thought exists is critical to its validity, and the criticisms thereof allow for the production of thought of substance.

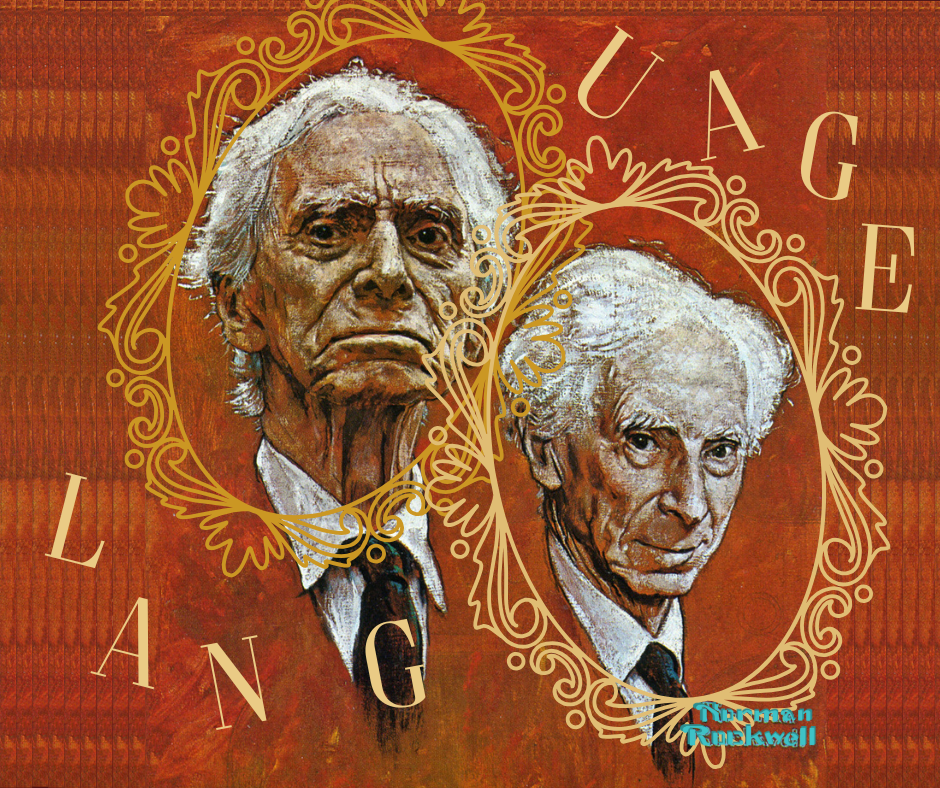

Perhaps the two most popular philosophers addressing this problem and its field were A.J. Ayer and Bertrand Russell, often credited with the introduction of linguistic influence on philosophy. Ayer, in his 1936 book Language, Truth, and Logic, divided statements he saw as worth pursuing and those he considered inutile pursuant to two qualifications: if the statement was analytic – true by definition or classification, holding some linguistic and semantic weight – or if it was testable in the physical world. If neither of these boxes were checked, there was no use deliberating the thought. Questions about alternate realities, life after death, God, etc., were to be immediately discarded. Russell, a brilliant mathematician and logician, was more concerned with the sense and syntax of a proof or set, using logic to arrive to a satisfactory conclusion, and suggested that rules or laws when referred to themselves are what result in paradoxes – like the statement this sentence is false – but was also famous for his encouragement of analysis on the pragmatics – the implications of language based on context – of a statement rather than jumping into the common binary of true-false in its meaning. If he had looked at A.J Ayer’s rule, he would have found it to be inapplicable to itself, but would not have necessarily invalidated it. He furthered that our language relied on logic rather than precision and analyzed the correlations between our realities and our descriptions of it.

Combining both their modes of thinking, we must look at the context, syntax, and language of an abstract statement before analyzing its meaning and worth, and then conclude whether or not it should be pursued. We should also keep in mind that this is a logical approach to language, which may therefore prioritize “making sense” over “holding truth”. Questions on realities beyond our own may not lead to a definitive answer (likely bearing fruit to even more questions), but its exploration needn’t be marked as useless. Philosophy that can only be deliberated with language and not demonstrations – meaning, abstract – could reflect more on the raw, unsupported views of people, than anything else. Their consideration is as much a look outwards as inwards. That is their true value.