Kara-mess-ov: Family Ties and Tangled Minds

Part I of VII | Introducing the Characters and Character of Dostoevsky in his "The Brothers Karamazov".

Introduction

The Brothers Karamazov, by Fyodor Dostoevsky, is, in almost any manner of print, close to 1000 pages long (except for those with two-column pages, where the number nears 480). Dostoevsky wrote this epic following the loss of his son, whom he named the arguably most-loved character in the story after; additionally, the father figure of the three main characters shares a name with Fyodor himself. It’s therefore plausible that the story cuts a mirror reflection into the life of the Russian author, and it is of consequent importance to analyze his own life as relevant to The Brothers Karamazov before delving into the book itself. By drawing parallels between the famously devoutly religious Orthodox Christian writer and a book discussing contrary views on that same subject, a book often described as “the pinnacle of Russian literature” unveils itself, and allows for the reader to explore three worlds: of Russia, of the pious, and of the painfully human.

It is worth noting that this article sidesteps the popular notion that Dostoevsky created dark, sad, or depressing literature. Rather, and especially with The Brothers Karamazov, it’s the sober realism that shrouds the plot, and if one remains reasonably optimistic in acknowledging the fact, his work becomes (even more) beautiful. An example: Ivan, the second-born and more intellectual or academic character in the book, states that “The more I love humanity in general, the less I love man in particular” – a true statement, sad to an idealist, cynical, possibly, to a misanthrope, but bittersweet to a realist. The core of the phrase is about love and its presence in humanity as a whole, while acknowledging (or arguing) the existence of individual wickedness.

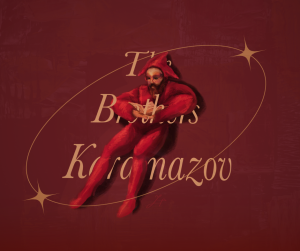

The title image of this article is an original (!!) recreation of the painting of the Polish jester Stańczyk after realizing the loss of a Commonwealth to Russia, juxtaposing a popularly-cheerful character with (and in) a context of great peril. Many in the background of the painting are oblivious; the jester sits alone. The drawing was made in Stańczyk’s likeness, but with Dostoevky’s face replacing his own, and a book (TBK), rather than a letter, in his hands. Why is that?

Dostoevsky: A Pseudo-Biography

This too-brief segment focuses on Dostoevsky’s life as it inspired The Brothers Karamazov. Where he was born (Moscow), then, is of lesser consequence than how his first novel, Poor Folk, exposed him to the literary upper class of Russia, which would then reject him following the unsatisfactory reviews of his subsequent works, resulting in the experience he would draw from when painting the profusely educated. His prized education, coupled with his exposure to the lower classes, pertains to the myriad of perspectives in the story more than his denial from the higher circles of society. His involvement with French socialism, due to its continuous occurrence in the minds of a multitude of his European-influenced characters – most notably Miüsov, the cousin of Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov’s first wife – is as relevant as his romantic involvement with a “wild” Polina Suslova while he was (albeit unhappily) married to Maria Dmitrievna Islaev. But his famous terrifying brush with death, in which Dostoevsky, blindfolded and awaiting imminent execution, was saved by a last-minute order from the Tsar, had lived a moment when every thought, every breath, could reasonably be his last. The existential panic that ensued bled from his mind to his pen, and drowns almost every religious theme in The Brothers Karamazov as it does his later works. When writing this book, Dostoevsky’s son Alexey died, and the writer sought a monastery to find solace. He later mocked its decadence, viewing it as contradictory to its teachings – this thought reappears on separate occasions implicitly and directly in The Brothers.

Dostoevsky’s life was one plagued by poverty, anxiety, and loss; The Brothers Karamazov, a part of a series discussing God’s existence, should have reasonably been shrouded in terrible darkness or cynicism, as a correlation of this nature between author and works of this type are so common. It is, in my opinion, Dostoevsky’s intelligence and will to conduct a discussion rather than an argument that separates TBK from the tragedies of his own life – the tragedies that present themselves within the novel are glimpses of those he has faced, but do not overshadow the true nature of The Brothers Karamazov as he intended it:

It is a discourse on God, a question of existence, and an answer found scattered in its pages.

The Main Characters

The fundamental aspect of a discussion is not the achievement of a decisive conclusion, but the diversity of the views that constitute a debate. Should two perspectives agree with one another completely, a discussion may last a sentence. Should a number of perspectives find no common ground, the discussion may never end (Dostoevsky’s does, at some point far down the line). The following characters are or were at some point in The Brothers Karamazov relevant, participating, or the subjects of a discussion concerning the Church, religion, and/or God.

Note: As middle names, ____-vich or _____-vna mean “the son/daughter of _____”; “Ivanovna” means “the daughter of Ivan”.

Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov,

in this article (and to a certain extent in Part I, Book II, Chapter II: “The Old Buffoon”) compared to a Jester, is ridiculed by the narrator, an apparently semi-omniscient (inferred to be reflecting on the story following the events that took place within it, and hinted to be a member of the monastery Alexey joins). He is in love with Grushenka, also his son Dmitri’s love interest. His murder by |SPOILER his adopted/illegitimate son Smerdyakov| is a pivotal moment in Book IX and onwards, and his involvement in the religious conversations of Book II appears as a form of a chaotic derailment of respect for the Church, but sheds a humbling light on much of our population today.

Hedonistic

- Began poor, used his marriages and connections to die with 100,000 roubles

- Did not care for his children young; despises Dmitri, gets along with Ivan, and loves Alexey

- Drunk, often depicted with Dionysian imagery

- Dionysian: fun vocabulary word, in this context meaning associated with the pursuit of pleasure, often involving wine or alcohol

Dmitri/Mitya Fyodorovich Karamazov

is the eldest son of Fyodor Pavlovich, and lives upon his emotions, wills and needs; in a fit of anger, he fights a captain and is sent off from the military; in a sudden surge of romance, he chases after a sensual Grushenka (likely inspired by Dostoevsky’s own Polina), and simplifies questions of morality and faith (Part I, Book II, Chapter VI) in what is almost concerningly similar to naïvety. His trial for |SPOILER his father’s death| brings to him a similar experience to Dostoevsky’s condemnation to death by firing squad (Part IV, Book XII, Chapter XIV), from which both derive existential crises. Fyodor could be argued to be a progression of his son, soon to be led astray from the Church by women and wealth, but it is his revelation upon having his senses crash upon him at his sentencing which brings to question the importance of Faith when chased into a dead end.

Sensualist/Experiential

- Conned by his father out of his inheritance, despises Fyodor

- “Innocent”, and almost Epimetheistically* spontaneous in his love-and-hate affairs

- Alternates between attempting to buy off his marriage, chase his lover, and enact revenge on his father

*I (am proud to have) made this word up. It is based on Epimetheus, god of hindsight (his name literally means “afterthought”), who allowed for both his marriage with Pandora and for her jar to be unsealed, despite the warnings of his more diligent brother Prometheus’ warnings. The word is used to characterize a lack of attention to the future or the repercussions of a given action or environment.

Ivan Fyodorovich Karamazov

is the second-born son of Fyodor Pavlovich, and described as “reserved, a bit morose”, recognized as a genius by Pyotr Alexandrovich Miüsov, who raises him and his younger brother Alexey as a response to Fyodor’s negligence. Ivan writes an article on the merits of ecclesiastical (relating to the Christian Church) courts, the arguments of which are frequently discussed in Part I’s Book II (Chapters V, VII) and Book V (Chapters V-VII). Ivan’s position on God and Faith is largely a pragmatic one, which leaves him conflicted spiritually, resulting in his famous “Grand Inquisitor” self-debate. He, surprisingly, is noted to be most like Fyodor, which may be a religious comparison.

Skeptic

- The most educated Karamazov, writes for publications despite his stature as a natural science student

- Interestingly – and this is very well-written – does not believe in what he argues; pessimistic

Alexey/Alyosha Karamazov

is the youngest of the Karamazovs; he joins a monastery and idolizes its Elder Zossima, resulting in his devout and pious nature. He is loved by all, likely due to his frequently-proclaimed (almost permeating) kindness and will to do good, but it is stated that “should he not believe in God and immortality, Alexey would immediately have been an atheist and a socialist,” which can be interpreted based upon the definition of socialism denoted by Dostoevsky – most likely negative, as Dostoevsky, devout Orthodox Christian, believed it to be incompatible with his religious beliefs – and which creates a transitional boundary between Alexey and Ivan, the latter of which could be characterized as a disillusioned, atheistic (though he can be argued to have been more agnostic) and socialistic form of his younger brother.

Orthodox Christian & Youth

- Zossima, upon his death, sends him out “sojourn the world”, leading Alexey to befriend children, who have their own adventures in Part IV, Book X, and the Epilogue

- Alexey is frequently confided in, almost reminiscent in the way of a confession, by his family and friends, standing firm in his morals and beliefs in the face of contrasting arguments

- In conversations, Alexey is often the voice of the Orthodox Church, and “higher morals”

The Minor Characters

This list most notably doesn’t include the female or young characters of the novel, for the reasons that their appearance is most often used as a catalyst for the development of the main characters’ ideologies and perspectives on the world, and so their definitions in this list would have to largely be found in the paragraphs under the names of Dmitri, Ivan, Fyodor, and Alexei. That being said, those below present their own unique views, religious and social, that further plunge this story into the mess of arguments and thoughts that make it legendary.

Father Zossima

is the Elder of Alexey’s (and the narrator’s) monastery, who passes away in the beginning books of the story. His influence on Alexey is great, and he is the “wise man” figure to which many of the characters confess to. His voice is emblematic of the Church, but differs from Alexey’s in his arguments for the Church above all, whereas Alyosha can be argued to stand more for the “good” than the religious, despite following both. For the sake of simplicity, the clergy is associated in this article with his views.

Orthodox Christian & Elder

- Is viewed as a prophet by many, and is both revered and hated; his chambers are room for many existential discussions (Part I, Book II)

- His prophetic rulings and declarations, especially in Part I, Book II, are controversial, at times offering solace rather than a solution

- A comparison can be made between religious and social morals in his pardons issued in Part I, Book II, Chapters III-V)

Pyotr Alexandrovich Miüsov

is a guardian figure of the younger two Karamazovs, and always clashing with Fyodor Pavlovich; as a relatively wealthy, European man, his views are more progressive and fervently in disaccord with the views of the Church in its scope of power (Church vs State & ecclesiastical courts) and results of lack of Faith (Book II specifically).

Progressive

- His conflict with Fyodor results in the entertaining of the latter, and his “European” views are actually more similar to Ivan’s later views in the story (~Book V, Book XI) rather than his preliminary proposals in Book II

- The only character to really be painted as a foreign, or European-educated man, his views also represent a note of distaste between perceived French ideals and Russian ones

Pavel Fyodorovich Smerdyakov

referred to only as Smerdyakov, is a rumored illegitimate son of Fyodor | SPOILER: and ultimately the one responsible for his death |. Ugly, hated by all (including every reader to have picked up The Brothers Karamazov), and conniving, one can only empathise with the abandonment he faced from both his parents. A servant of the Karamazov house, once more, nobody likes him. Perhaps it’s due to this that his views align with the more antagonistic (at least to Dostoevsky) philosophy: Nihilism.

Nihilist/Devil’s Advocate

- Consumed by rage, his interactions (specifically with Ivan) present themselves as rants to burn the world around him

- |SPOILER: His motivations for killing his rumored father include having been pulled by Fate, helpless to stop It/Her; though this is more Fatalist (think: Fate+alist) than Nihilist, coupling his argument with his burn-all mentality presents an image of chaos more arguably Nihilistic. Write that in your high school paper!|

The Conclusion

The names having been written, the context having been given, the spindle is ready; only the symbols and revelations of the book remain to be woven into words. Less poetically, here is The Boston Hound‘s Table of Contents for articles pertaining to The Brothers Karamazov, for which when reading it’s recommended keeping this page open.

TBH's TBK: A Table of Contents

Links coming soon!

I. Context & Characters

Descriptions of religious figures in the story, followed by their “classifications” or affiliated schools of thought

II. The Church vs the State

The merits of ecclesiastical courts and religious versus institutional law: Ivan, Alexey, Zossima, Monks

Or, the Bishop vs. the King

III. Morals & Freedom (in and out) of the Church

The contradictions of morals encouraged in the name of the Church and its punishments: Zossima, Peasants, Ivan

The restrictions of the Church in the seeking of freedom: Alexey, Zossima, Monks, Miüsov

Or, the Pawn vs. the Bishop

IV. A World Without Faith?

Arguments to and for the notion that a lack of faith results in inevitable evil and chaos: Ivan, Miüsov, Dmitri, Fyodor, Monks

Or, the Bishop vs. the Knight

V. Uncertainty vs Blind Devotion

Notes on Ivan’s uncertain, almost agnostic, dialogue in the face of Alexey’s devout faith: Ivan, Alexey

Or, the Knight vs. the Pawn

VI. A Word on the Grand Inquisitor

Lessons learned from The Grand Inquisitor: Ivan, Alexey

Or, the Rook

VII. Conclusion: The Chess Set

Takeaways, Summary, Rating, Original Argument, and Downloadable Guide

Fyodor Dostoevsky

@wordcount_publicenemy1

Elements of Works: Existentialism and Russian Psychological Realism